Materials and Technologies for Emerging Devices

It’s fascinating to learn how the laws of Physics vary from the macroscopic world to the microscopic world. Some of the physical properties that we often ignore in macroscale become significant in nanoscale, while a few other properties become less noticeable in nanoscale but are highly crucial in macroscale. Synthesizing, manipulating, and analyzing nanomaterials using advanced technologies open a wide range of opportunities to seek answers to some of the fundamental scientific questions. The challenges remain how to synthesize functional nanomaterials, their assembly, patterning, and their applications for the betterness of science and society.

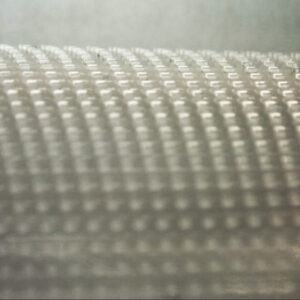

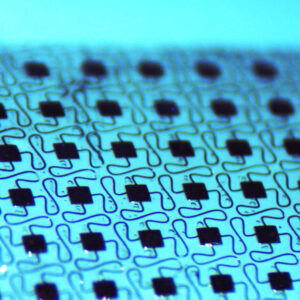

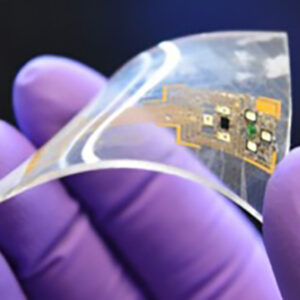

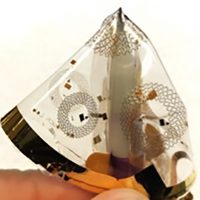

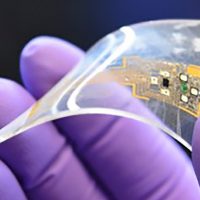

On the other hand, we are going through a transition period from rigid electronics to flexible and soft electronics. And, this transition demands new types of materials than that of conventional electronics. For example, silicon (Si) is one of the primary materials in modern electronics, which is rigid. However, emerging soft devices explore flexible and soft materials such as polyimide or silicones. Transitioning from rigid materials to flexible and soft materials open a wide range of potential materials because of the vast world of natural and artificial polymers. Also, the mechanical flexibility and stretchability can be achieved using rigid materials based on geometric patterns and mechanics of thin films. These issues of selecting materials for emerging devices require fundamental studies of materials properties, their limitations, and their benefits of using in the devices.

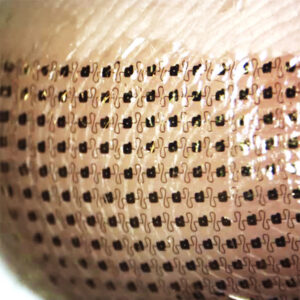

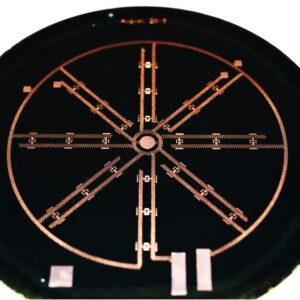

The other paramount concern of the emerging flexible and soft devices is reliable manufacturing. Currently, there exists no universal manufacturing process to realize soft electronics when compared with the rigid printed circuit boards (PCB) technology. Moreover, the integration density and complexity of the demonstrated soft and stretchable devices remain far behind conventional electronics. To exercise the full benefits of this emerging technology for real-life applications, the technology must be matured and reliable and need to be compatible with industrial manufacturing. The big question is- how to engineer a universal manufacturing method that is compatible with the industrial production of highly integrated soft electronics! Can we devise a stretchable printed circuit board (SPCB) technology? Is it possible to engineer a hybrid technology that will use existing rigid surface mount devices (SMD) in soft and stretchable circuits?

The additional manufacturing problem is the assembly of the components in the soft circuits and their packaging. Conventional robotic pick-and-place machines are mostly limited to assemble components onto rigid substrates. Their yield is also low when the dimensions of the chips or dies become microscopic. Is it possible to engineer a self-assembly technique that can overcome many of these limitations- can assemble microscopic components with high yield regardless of the mechanical properties of the substrates?

It’s fascinating to learn how the laws of Physics vary from the macroscopic world to the microscopic world. Some of the physical properties that we often ignore in macroscale become significant in nanoscale, while a few other properties become less noticeable in nanoscale but are highly crucial in macroscale. Synthesizing, manipulating, and analyzing nanomaterials using advanced technologies open a wide range of opportunities to seek answers to some of the fundamental scientific questions. The challenges remain how to synthesize functional nanomaterials, their assembly, patterning, and their applications for the betterness of science and society.

On the other hand, we are going through a transition period from rigid electronics to flexible and soft electronics. And, this transition demands new types of materials than that of conventional electronics. For example, silicon (Si) is one of the primary materials in modern electronics, which is rigid. However, emerging soft devices explore flexible and soft materials such as polyimide or silicones. Transitioning from rigid materials to flexible and soft materials open a wide range of potential materials because of the vast world of natural and artificial polymers. Also, the mechanical flexibility and stretchability can be achieved using rigid materials based on geometric patterns and mechanics of thin films. These issues of selecting materials for emerging devices require fundamental studies of materials properties, their limitations, and their benefits of using in the devices.

The other paramount concern of the emerging flexible and soft devices is reliable manufacturing. Currently, there exists no universal manufacturing process to realize soft electronics when compared with the rigid printed circuit boards (PCB) technology. Moreover, the integration density and complexity of the demonstrated soft and stretchable devices remain far behind conventional electronics. To exercise the full benefits of this emerging technology for real-life applications, the technology must be matured and reliable and need to be compatible with industrial manufacturing. The big question is- how to engineer a universal manufacturing method that is compatible with the industrial production of highly integrated soft electronics! Can we devise a stretchable printed circuit board (SPCB) technology? Is it possible to engineer a hybrid technology that will use existing rigid surface mount devices (SMD) in soft and stretchable circuits?

The additional manufacturing problem is the assembly of the components in the soft circuits and their packaging. Conventional robotic pick-and-place machines are mostly limited to assemble components onto rigid substrates. Their yield is also low when the dimensions of the chips or dies become microscopic. Is it possible to engineer a self-assembly technique that can overcome many of these limitations- can assemble microscopic components with high yield regardless of the mechanical properties of the substrates?

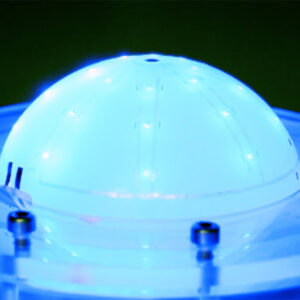

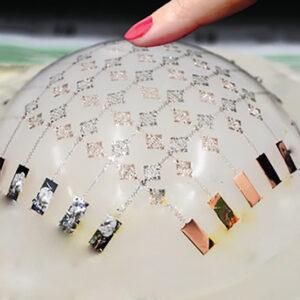

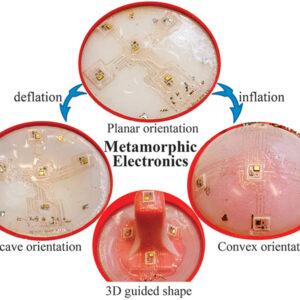

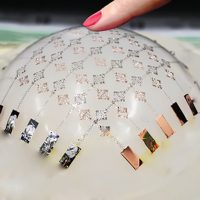

Finally, this emerging technology enables a new era of electronics where the devices can be shape-adaptive, can be “Metamorphic”. Developing such electronics requires designing devices that can sustain different strain at different locations on its surface to accommodate desire shapes. Such metamorphic electronic systems with integrated functionalities that can achieve many other shapes than just sphere. Once fully developed, most electronic systems known to humankind could morph to take on new exciting form factors. We could demonstrate many fascinating shape-adaptive devices and functions. Imagination is limitless!

My general research interest lies in the field of materials engineering and manufacturing technologies to realize functional devices focusing applications in healthcare, bioengineering, consumer electronics, sensors, actuators, wearable devices, robotics, virtual reality, haptics, and many others. I also posses research interest in fundamental studies in nanomaterials, materials synthesis, semiconductor materials and devices.

Materials Engineering and Nanomaterials

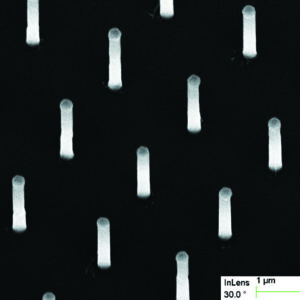

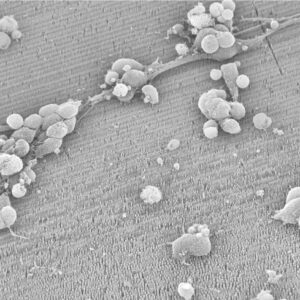

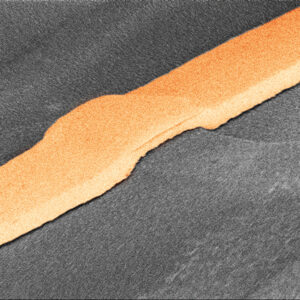

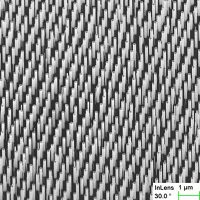

Materials science and engineering are the core of modern technologies and devices. Fundamental studies on materials science also advance our understanding from atoms to the universe. This is also an essential part of the research to innovate new technologies or devices. For the last few decades, materials science combining with nanotechnology accelerated a new approach to developing methods to engineer novel devices. This also matured our scientific understanding of nature and materials in nanoscale. Blessed by nanotechnology, III-V materials have seen a significant advancement resulting in a new era in electronics, photonics, sensors, and many other areas. Scientists have also invented other novel materials with intriguing properties such as Graphene, Fullerenes, and others. This combination of materials engineering and nanotechnology also enabled new scopes in device design. For example, the world has seen new consumer electronic devices based on quantum dots. 1D nanowires or nanotubes or nanorods have also attracted prodigious interest to the scientists for their unique characteristics.

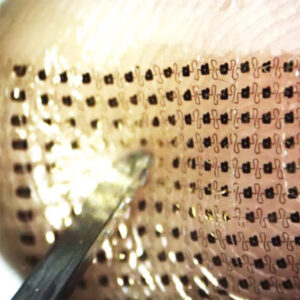

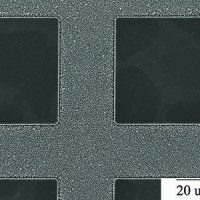

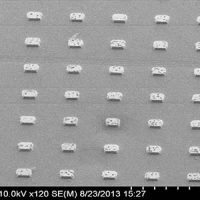

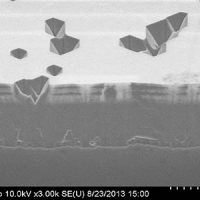

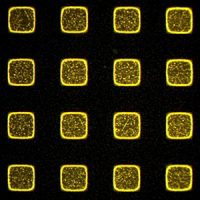

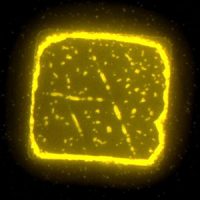

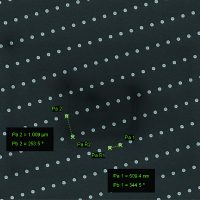

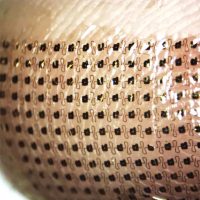

By being a Physicist, I am inherently interested in nanomaterials, semiconductor materials, and devices. My research in this direction includes synthesizing Si nanowires using metal-assisted chemical etching (MACE), realizing highly ordered Au nanoparticles using high-resolution electron beam lithography and patterning techniques, epitaxial growth of ordered GaP and InP nanowires based on vapor-liquid-solid (VLS) method using metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). I have also attempted to grow localized GaN epitaxial layers using MOCVD. Many of these devices have been used in bioengineering and electronics applications. Read more

Emerging Soft Electronics

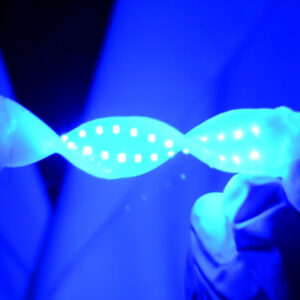

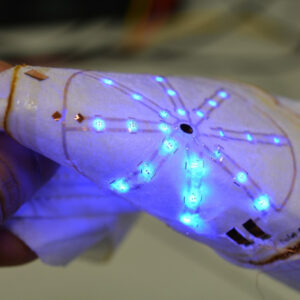

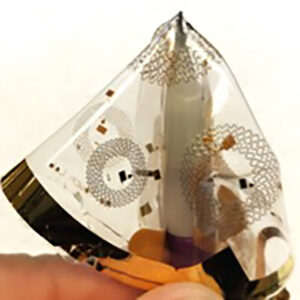

A dramatic increase in research activities has been perceived for last decade to enable mechanically stretchable and deformable functional electronic devices. Consequently, a large number of stretchable devices have been realized demonstrating a wide range of diverse applications that includes smart clothing, conformable photovoltaics, optoelectronics, digital cameras, electronic skins, stretchable batteries, soft robotics, actuators, wearable electronics, metamorphic electronics, edible electronics, acoustoelectronics, health monitoring devices, to give a few examples. Most of these demonstrators often use highly specialized technologies and unconventional materials that make these technologies more interesting for research, but less favorable for industrial production for mass people.

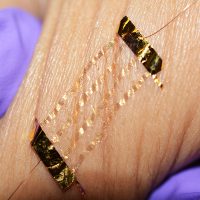

My research is deeply motivated by the myriad promises of emerging soft electronics and devices. Mechanically soft devices closely match to biological tissues and also can conform to complex surfaces. This fascinating characteristic of soft electronics opened a wide range of potential applications that rigid conventional electronics cannot provide.

Soft Electronics: Wearable to Metamorphic

One of the primary motivations of developing soft and stretchable electronics is their unique mechanical properties. Soft devices can conform to the skin or any other complex surfaces, which provide opportunity to intimate contact to the body for long run. This is important for uninterrupted continuous health monitoring.

My research is deeply motivated by the myriad promises of emerging soft electronics and devices. Mechanically soft devices closely match to biological tissues and also can conform to complex surfaces. This fascinating characteristic of soft electronics opened a wide range of potential applications that rigid conventional electronics cannot provide.

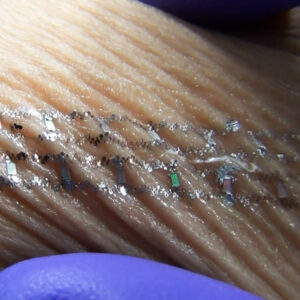

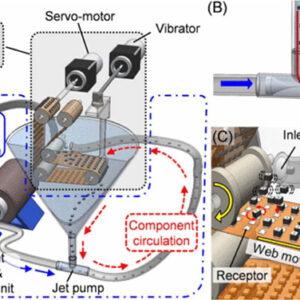

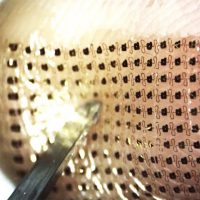

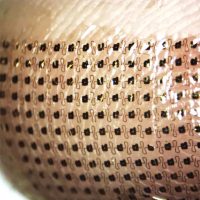

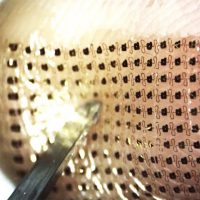

Fluidic-Self-Assembly

One of the main obstacles to the continuation of scaling of modern electronic systems can be found in the minimal component size that can be assembled and electrically connected effectively. Current technology for chip-scale packaging and assembly relies on robotic pick-and-place. Microscopic chips and higher alignment accuracy decrease the throughput dramatically and can generally not be assembled effectively. Moreover, robotic pick-and-place faces challenges in cases where the substrates are not rigid and perfectly planar. An alternative assembly process that enables assembly on any substrate (hard, soft, flexible, stretchable) and topology (curved, convex, concave, etc.) are in high demand.

Researchers have been constantly seeking an alternative to serial robotic pick-and-place on a single component basis, and several highly-parallel assembly techniques have been proposed. Two novel assembly options have emerged.

BioEngineering

One of the main obstacles to the continuation of scaling of modern electronic systems can be found in the minimal component size that can be assembled and electrically connected effectively. Current technology for chip-scale packaging and assembly relies on robotic pick-and-place. Microscopic chips and higher alignment accuracy decrease the throughput dramatically and can generally not be assembled effectively. Moreover, robotic pick-and-place faces challenges in cases where the substrates are not rigid and perfectly planar. An alternative assembly process that enables assembly on any substrate (hard, soft, flexible, stretchable) and topology (curved, convex, concave, etc.) are in high demand.

Researchers have been constantly seeking an alternative to serial robotic pick-and-place on a single component basis, and several highly-parallel assembly techniques have been proposed. Two novel assembly options have emerged.

Optical Tweezers

Optical Tweezers is an important tool that uses highly focused laser beam to trap and manipulate nanometer and micrometer-sized particles. Optical tweezers has a wide field of applications including biology, chemistry and physics. Manipulating micrometer sized beads, trapping atoms, sorting cells, measuring forces as weak as a few piconewtons – these are just a few of those applications.

Typical optical tweezers setup requires very expensive and controlled optical tools. However, lab-based test set up can be developed using cheap diode lasers and an optical microscope. In a project, I developed such a set up to trap micro-particles. The project was carried out at the Lund University, Sweden.